On 11 March 2025 I plan on trying to be funny.

That's the date of the launch event for my book Everyday Jews at JW3, the Jewish Community Centre for London. Somehow, rather than being content with a free event over lukewarm white wine and a few nibbles, I have set myself the challenge of convincing people to pay for this:

To mark the launch of Dr Keith Kahn-Harris's new book Everyday Jews, come and join the author and friends for an evening of silliness with a serious message.

At a heavy and significant time for the Jewish people, Dr Kahn-Harris and guests will remind us that Jewish life can also be trivial and parochial. There will be interesting talks on boring Jewish things, there will be affectionate celebrations of Jewish communal incompetence, there will be Palwin cocktails, and an Adon Olam karaoke session.

It will be fun and I would urge anyone reading this to consider booking. But it does raise an awkward question that's been stuck in my head for a while:

What gives me the right to think I am a funny guy?

Something has happened to me in the last twenty or so years. It started with the odd witticism in lectures and in my writing and grew from there. Over time I have found myself authoring a book with an eccentric premise and pushing myself to be ever wittier. Sometimes I have pulled it off and made people smile or laugh, other times I have amused myself primarily (as in my 'Impossible Books') or tried a bit too hard and failed (as with my 'Best Water Skier in Luxembourg' project).

I'm not a pro. I'm the very definition of 'hit and miss'.

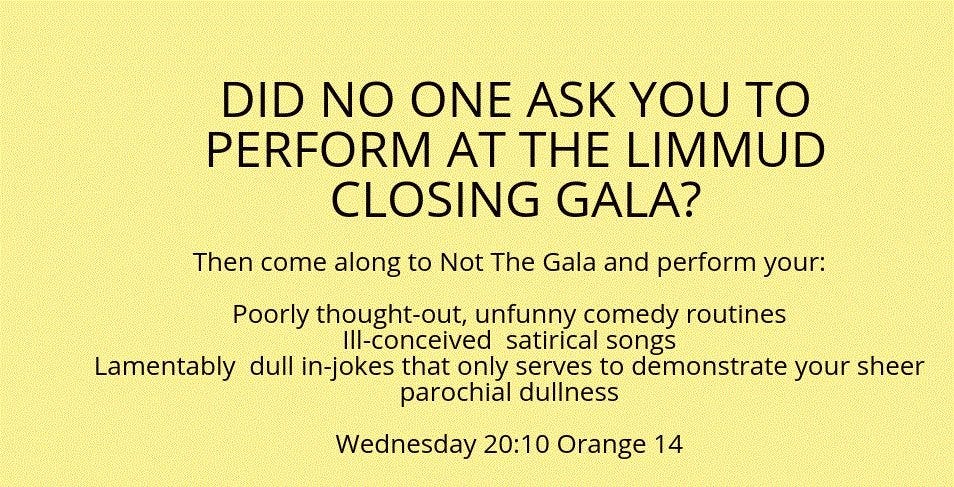

Sometimes that erraticism can be a glorious thing. Over the last decade or so, I have teamed up with my friend Dan Jacobs to help run the alternative to the main Gala at Limmud Festival. 'Not The Gala' as it is known, is chaotic, foul-mouthed and wilfully under-rehearsed. When it works, it's joyously playful and delightful. Over the years I have fed Jeremy Corbyn's 'special mayonnaise' to a senior member of the Jewish Labour Movement, and organised a Rothschild vs Soros arm-wrestling bout. Dan and I have pushed each other to ever-greater heights of public immaturity, even as we rush headlong towards the business end of middle age.

When it doesn't work though...

Incoherent vulgarity sometimes overwhelms me. Ideas that sounded funny in the pub prove awful in practice. Satire can become outright nastiness. And playful incompetence can sometimes cross over into bloated self-indulgence.

At the December 2024 Not The Gala, Dan Jacobs and I officially retired. We chose two young people at random to run it in future and anointed them with Diet Coke as a member of the audience sung 'Zadok The Priest'. Amazingly, one of them plans on actually taking it on.

My experience with hit-and-miss wit and ill-prepared comic skits has taught me something about the desire to be funny: It's a dangerous desire. The experience of making a room full of people laugh - even if it only happens once - can be intoxicating, and that can lead to appalling hubris and desperate attempts to chase the thrill.

The problem is that the modern phenomenon of the professional comedian - a person whose job is to be consistently funny - has warped how we understand humour. Most of us, even the most apparently over-serious of us, sometimes raise a smile. Humour and wit is part of everyday interaction, albeit an occasional one; there was laughter long before there was a discipline of comedy. But what the existence of comedians and comedy as genre has done is to set a dangerous precedent; that it is possible and laudable to aspire to be relentlessly and endlessly funny. And the corollary is true too; those of us who are not comedians can occasionally 'do' funny but cannot 'be' funny.

There has never been a more accurate dissection of the modern desire to be funny than the UK version of The Office. The character of David Brent offers a case study of what can happen when the desire to be funny overwhelms a regular person. Before the documentary camera crew came to film at the Wernham Hogg office, Brent was likely a common or garden office joker; sometimes tedious but basically benign, he was still able to get the regular business of the workplace done to a level that led to his promotion to manager. Once the cameras arrive, he starts to see himself as a comedian and 'entertainer'; he speaks of 'my comedy' and, in his own head, crosses the line separating those of us who can sometimes do funny from those who can be funny as a profession.

There is one scene in particular that makes me wince. Brent recalls how, at ‘the Coventry conference’, there was a last night revue where he did impressions. One was of the conference coordinator Eric Hitchmo, whose catchphrase was, apparently, 'I don't agree with that in the workplace'. Brent performed the catchphrase as Columbo, Basil Fawlty and others. In the scene he recalls this, you can see his pleasure at having made people laugh. Yet when he tries to repeat his conference triumph in front of people who don't know him, it's a total disaster.

That could be me if I made the mistake of believing that Limmud Not The Gala was proof of my comic genius.

As I have experimented with wit and humour in the last couple of decades, I have tried to remember what happened to David Brent. Larking about at Not The Gala may have sometimes made people laugh, but there is a big difference between the benign environment of a community conference and the savage judgement of a comedy club open to all. If I actually wanted to become a comedian, it would take years of toil with absolutely no guarantee that I would actually make anyone laugh other than myself.

Still, I think there may be an underappreciated value to the kind of occasional hit-or-miss humour I sometimes indulge in. Or at least there is when it comes to Everyday Jews. In my book I have tried to argue that the relentless and very public brilliance of the Jewish people has caused Jews and non-Jews to neglect the fact that Jewish life can be as mundane and mediocre as any other kind of life. At a time when Jews are constantly in the spotlight, I've attempted to convince Jews and non-Jews that we can also be as humdrum as anyone else. Everyday Jewishness isn't awash with Larry Davids but David Brents.

A writer who can make your sides ache with laughter is not the kind of writer who should be writing a book on everyday Jewishness. A writer who can occasionally raise a modest chuckle is more appropriate. I was the right person to write this book as my capacity to amuse and to move is inconsistent. The joke that doesn't land, the witticism that baffles, the sly reference that is too obscure and idiosyncratic to even notice - that is the stuff of everydayness.

So on 11 March 2025 I will celebrate the inconsistent wit of the Jews by being occasionally funny. Do join me and let's revel in the disappointment together.

So sorry I missed that book launch!!!

Please find some way to come to Australia at some stage!