In praise of mundane anecdotes

How a mundane anecdote in Chris Frantz's autobiography is actually extraordinary

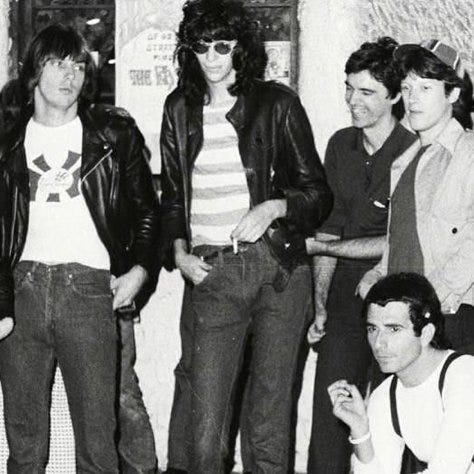

In spring 1977, Talking Heads toured Europe for the first time, alongside the Ramones. The whole thing was an incredibly exciting experience for the drummer, Chris Frantz. In his autobiography Remain in Love: Talking Heads, Tom Tom Club, Tina, Frantz recounts the following anecdote of checking into the Hotel Wiechmann before their show in Amsterdam:

Tina and I climbed the very steep and narrow stairs right behind Joey Ramone. We had tiny rooms on the fourth floor and with our duffel bags it was a real hike. I remember collapsing onto the bed with Tina to take a short nap when there was a knock on the door. Getting into the tiny room was no problem, but there was no room to open the door from the inside without standing on the bed. It was Joey [Ramone], who wanted to make sure that we didn’t forget him when we left for the show. I assured him that we would never leave him behind.

…and that’s it.

It’s hard to know why this anecdote survived the editing process for the book. It tells us that Dutch hotels - or this particular Dutch hotel - can have steep and narrow staircases which can be annoying to navigate during the rigours of touring. It also tells us that Joey Ramone was anxious about being left behind on tour, or was anxious on this one particular occasion, or was not anxious at all but found Frantz to be a dependable person to rely on.

The inclusion of the anecdote becomes even more mysterious when you consider that Remain in Love is very far from being a boring book. Talking Heads were an extraordinary band and the fractious relationship between Chris Frantz, his wife and bassist Tina Weymouth, and David Byrne, is fascinating (if often uncomfortable) to read about.

I’d probably have forgotten the Amsterdam anecdote by the time I finished the book, were it not for another anecdote towards the end. Sometime in the early 90s (the dating isn’t clear) , with Talking Heads on permanent hiatus, Frantz started to unravel:

Let’s just say that even I realized that I had developed a bad problem with cocaine. I was in a special program for successful people with drug problems. Tina was concerned that I might die, and I don’t blame her. I had been bingeing for years, but mostly keeping it under control. Being in the music business, I could always tell myself that some other guy I knew was in much worse shape than I was. Tina took baby Robin to France for the summer of ’84 and asked me not to come. After she left I found myself buying an ounce of coke and not stopping until it was gone. I was up for nine days. Nine days wandering from party to party, club to club, without sleep and not going home except to take a shower and change my clothes. I was not all right. In retrospect, I realize that I was in mourning for the Talking Heads dream I’d had. I could see what was happening to us after so many years of hard work and dedication. I was sad and depressed, but of course cocaine and alcohol were not going to help. What helped me, finally, was Tina. She demanded that I get treatment or our marriage was over.

…and that’s it. The rest of the chapter talks about how he ‘renewed himself’ through sailing.

Whereas the Amsterdam anecdote appears to include too much information, the cocaine anecdote contains far too little. In a book that is as much about Tina Weymouth as Chris Frantz (or at least Frantz’s protective anger at how David Byrne treated her), this is the first we learn of any issues with their marriage. And it’s the last we hear too.

One could dismiss this asymmetrical approach to storytelling as bad writing. But ever since I read the book in 2020 (the year it came out) the Amsterdam anecdote has stayed with me, and not just because of the weirdness of its inclusion.

I think the reason why it’s stuck in my head is because it’s so rare to see that kind of mundane storytelling in a published book. The Amsterdam anecdote gives us a tiny glimpse into the reality of touring - checking in and out of hotels on a daily basis, trying to be in the right place at the right time - that we almost never get to see. Of course, I knew that this side of touring existed, but it is usually submerged in a sea of stories of sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll.

The anecdote also raises the question: How on earth did Chris Frantz remember it? And why did he remember it?

To try and answer that question I ransacked my memory for equivalent mundane anecdotes.

Here’s one I came up with:

In 1992 I backpacked around Israel with my friend Russell. He flew out the day before me for reasons I cannot recall, and checked into a hostel in Tel Aviv, reserving me a place for the next day. He rang me from a phone box to tell me where to go. My flight got in early and I caught the airport bus to the hostel on Bograshov Street. After I checked in, I met up with Russell, who was having breakfast, sat at the bar in the dining room. He looked tired as he asked the person serving, ‘can I have another cup of tea please.’

I have no idea why I remember that, but I genuinely do. As with Talking Heads’ 1977 European tour, I have plenty of interesting anecdotes from our 1992 tour of Israel. Yet I only have this one truly mundane anecdote.

The mundane somehow seems to escape the clutches of memory. Most of the time, I only have a hazy idea of the logistics of my youth. That feeling of not knowing how I managed everyday life - in the most literal sense of ‘manage’ - is compounded because, post-internet, I know longer remember how I made arrangements. For example, while I was an undergraduate (1991-1994), I had friends visit me who were studying at other universities. I didn’t have a mobile or a phone in my room and neither did they (and I wasn’t on email until the year after I graduated). The porter’s lodge at my College took messages and I suppose that’s how we organised things. How exactly we did it is not part of my personal history.

I tried again to find an Amsterdam anecdote from my undergraduate days; an anecdote that would encapsulate what my daily life was like. I couldn’t do it. I know, for example, that I tended to have dinner in the canteen at the same time each day and usually with a similar group of friends. I have vivid memories of eating in the canteen, of chatting with friends, even of some of the dishes I ate. Yet every time I tried to find a specific instance I come up with anecdotes that were in some way exceptional and, hence, memorable:

One evening I wasn’t able to sit with the people I usually sat with at dinner (perhaps I arrived late and all the places next to them were taken, I don’t remember). So I sat with a man and a woman in my year who I knew reasonably well and got on with, although I wouldn’t have considered them actual friends. They didn’t say I couldn’t sit with them but the conversation was halting and stilted. I found myself desperately trying to fill the silence, full of anxiety that they weren’t talking as they found me boring. Later, the guy came up to me in the bar and told me that I happened to have sit down with them just after they had decided to split up (I didn’t even know they were a couple). He was lovely about it and said I wasn’t to know.

It’s not a great anecdote and I wouldn’t include it in an autobiography. Yet it’s still too much of an exception to the rule to count as mundane.

My son is currently at university. I have been trying - often unsuccessfully - to restrain myself from giving unsolicited advice. At some point, though, I think I should tell him to try and consciously store up memories of everyday life. He will remember the good times and the bad times. He will also have composite memories of everyday activities like having dinner, but he won’t have specific memories unless he tries to retain them. Of course, if he does try to do this, the very act of trying to remember will mean that these memories will become extraordinary.

I suppose then, that Chris Frantz’s mundane Amsterdam anecdote is not mundane at all. Something about that incident made it extraordinary. And while its inclusion in his autobiography cannot really be defended on literary grounds, it might be defended on historical grounds; as a precious window into quotidian reality of a band touring Europe in 1977.

I quoted your penultimate paragraph to my son (also in college) and he acknowledged it was good advice.